As a mathematician, philosopher and astronomer, Hypatia was an influential figure in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, then part of the crumbling Roman empire. Though her Neoplatonic teachings were highly respected and her position seen as equal to men, her legacy is largely connected to her tragic death.

Born around the middle to late 4th century, she grew up around education. Her father was a teacher and Hypatia was taught like a boy, learning about philosophy, mathematics and astronomy – three disciplines closely connected in ancient times. Hypatia eventually took over from her father as head of the school.

Many were impressed with her intellect and leaders invited her council. She taught small groups of elite students and gave public lectures about Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle. Many of her students got to high places within Roman society, like Synesius of Cyrene, the bishop of Ptolemais, making Hypatia an influential figure in society.

“Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all.”

Hypatia

Her philosophy likely followed the Neoplatonic tradition of Plotinus. Though not much of her work survives, we find out about her teachings through her students and a few mathematical and astrological works discovered later. Neoplatonists strove to get closer to ‘the One’, considered to be the thing from which everything stems, the highest principle. Intellect and the soul comes from ‘The One’ and mediates with the material world. The body can only overcome the material world by getting closer to ‘The One’ by striving for philosophical virtues like contemplation, self-discipline and an ascetic way of life. Though this philosophy resembles monotheism, it is not Christian. Hypatia combined Christian and Greek heathen elements, making her teaching interesting to both groups. Her mathematician and astrological studies were a means of studying the world of the intellect, away from the material world. Some of her surviving work is a commentary on The Almagest, a treatise about motions of stars and planetary paths.

Her death in 415, by an incited mob of Christians, is often connected to her philosophy or the fact that she was non-Christian, but it is more likely that she was killed for political reasons. A power struggle arose between the bishop and the emperor’s prefect and, as a councillor, she was thought to be influencing the prefect.

Her legacy was, as I mentioned, often connected to either her death or that she was a woman. The painting below, by Charles William Mitchell, based on a book by Charles Kingsley from 1853, remarkably shows her “naked, snow-white against the dusty mass around”, highlighting ” her body – the exact thing she was trying to transcend with her work!

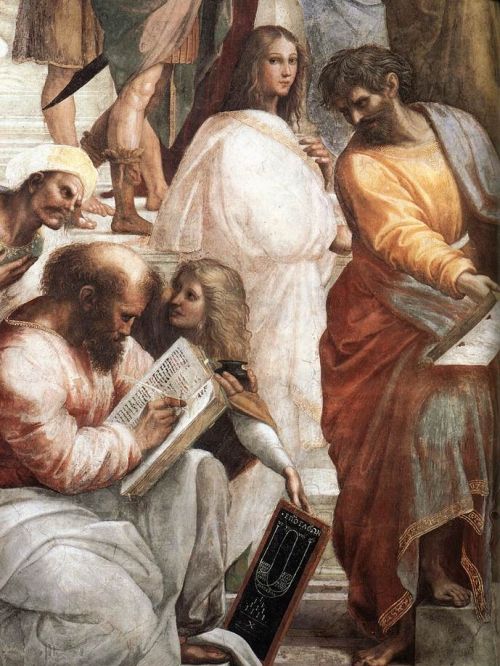

Her importance as a thinker was also noted, however, with her liking included in the famous ‘The School of Athens’ fresco in the Vatican by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael.

1. Hypatia. Charles William Mitchell, 1885.

2. The School of Athens. Raphael, 1509-1511.

3. Hypatia. Julia Margaret Cameron, 1867.

In recent years her role as a philosopher and powerful councillor has made her a feminist icon. There’s an American magazine called Hypatia about feminist philosophy and a Dutch Hypatia prize for the best philosophical work by a woman. In 2009 the final part of her life was made into a Hollywood movie, starring Rachel Weisz, called Agora.

Sources and other media:

- Book: ‘Hypatia of Alexandria’, Maria Dzielska, 1995.

- Book: ‘Hypatia’, Edward J Watts, 2017.

- Podcast: ‘STEMinists: Hypatia of Alexandria’, Encyclopedia Womannica, 2019: https://encyclopedia-womannica.simplecast.com/episodes/steminists-hypatia-of-alexandria-aZ5E333L.

- Article: ‘Hypatia van Alexandrië’, Filosofie Magazine: https://www.filosofie.nl/filosoof/hypatia-van-alexandrie/

- Film: ‘Agora’, Alejandro Amenábar, 2009.