Born as Mary Godwin, Mary Shelley was an author, mostly known for her novel ‘Frankenstein’. This gothic story about a scientist creating a cobbled-together monster that haunts him is often seen as one of the first works of science-fiction. Technology and scientific innovation are central themes in the story, as are the creation of life and responsibility for that creation. The book has never been out of print and continues to be relevant: in the recent film The Social Dilemma, an interviewee refers to the lack of control by large digital firms as the ‘digital Frankenstein’. ‘Frankensteining’ is apparently a verb commonly used in the Youtube DIY world or custom builds. The title is so well known, that the title is a byword in the English language.

Mary has every reason to be famous in her own right, but she could easily be (and sometimes was) overshadowed by those around her. Her mother, who died due to childbirth, was the well-known proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft who wrote The Vindication of the Rights Woman. Her father is the political philosopher William Godwin, author of Political Justice. And Mary’s lover and eventual husband was the famous Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

“singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire of knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes almost invincible.”

William Godwin, describing his daughter at age 15

Mary grew up in an unusual household. Her father’s guests and followers belonged to the intellectual elite and Mary regularly had dinner with the great minds of the time. She was a frail, unhappy child who felt guilt over her mother’s death (whose book she read) and was disliked by her stepmother. Though the informal upbringing Mary got wasn’t quite in line with what her bohemian mother had outlined, it was still unusual for a girl at this time. She read extensively and attended readings and lectures. Mary was bookish, informed and clever.

After returning from a stay in Scotland (probably for her health) she met one of her father’s political followers: the posh but anti-establishment poet Percy Byssche Shelley. He was in his early twenties, a radical, an atheist, a vegetarian (very unusual for that time) and married. But the two still fell for each other when she was just 16. As a believer in free love, Percy had no qualms to start a new affair. For Mary, it was Percy’s “wild, intellectual, unearthly looks” that got her heart racing. The story goes that they first had sex on Mary’s mother’s grave. Oh so very goth.

Together with Mary’s stepsister, Claire (who spoke French), the young couple ran away to France and aimed to walk to Switzerland (through a French countryside ravaged by the Napoleonic wars). One they got there, however, they’d run out of money and returned to England. Upon their return, Mary was pregnant with Percy’s child and they were ostracised by society, as they were unmarried. Hypocritically, Mary’s father used to be a believer of free love, but not when it concerned his daughter: they only reconnected when she was married. Meanwhile, the couple was in constant debt and had to deal with the death of their prematurely born daughter. This was not comfortable living. They eventually married in late 1816, after the tragic suicide of Percy Shelley’s deserted first wife, Harriet. Shelley is not always good news for his women.

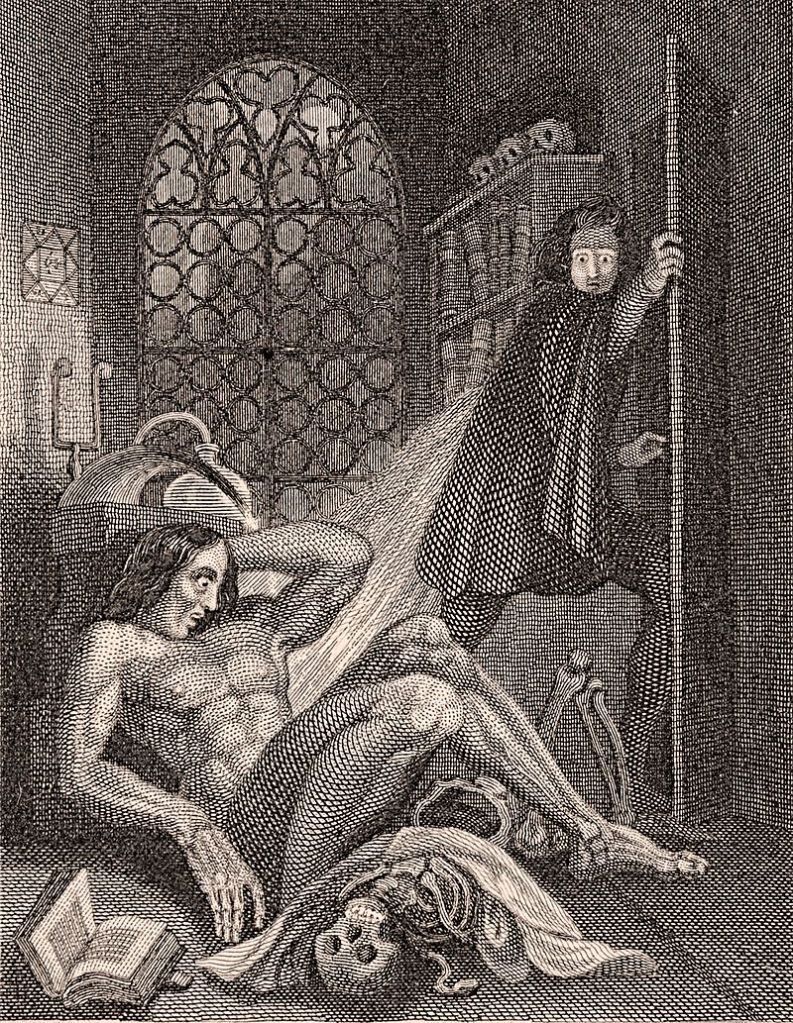

Earlier in 1816, the Year of No Summer, the couple famously spent the summer with the famous poet Lord Byron in Switzerland. Claire, the previously mentioned half-sister, was in the midst of a fling with Bryon and asked them to tag along. That year the atmosphere was dark and heavy with the volcanic ash from an outburst in Indonesia. Stuck inside, Byron set a ghost story challenge. This resulted in the houseguest Dr Polidori coming up with his idea for his 1819 novel The Vampyre, a precursor to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and for Mary to dream up Frankenstein’s story. The novel, titled ‘Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus’, was published the following year, when Mary was just 19.

The work is often called a masterpiece. It touches the magic of creation, control (or lack thereof), exclusion and loneliness, the responsibility in scientific progress (overreaching? Arrogance maybe?). Her monster is a complex being. It claims to be turned into a monster by its creator and society, only becoming monstrous by the treatment he gets from others. Though the story is of course fantasy, there are many elements from Mary’s life found as themes of the book.

During their summer in Switzerland, the men reported having serious discussions amongst each other about ‘the principles of life’, without considering, it seems, to ask the one person in the room who had actual experience with these principles: Mary. She had already given birth twice and lost one of these children – maybe she could have provided valuable insights about such principles in their conversations?

I have good dispositions; my life has been hitherto harmless and in some degree beneficial; but a fatal prejudice clouds their eyes, and where they ought to see a feeling and kind friend, they behold only a detestable monster.

The monster to the blind man in Chapter 15

In fact, the loss of her child can surely be connected to the concept of Frankenstein’s monster. She described dreaming of trying to reanimate the baby they lost with the warmth from the fire. A century before, the ‘scientist’ Luigi Galvani had done experiments with sending electric currents through dead body parts, causing these to twitch. This practice, called galvanism, gave rise to Mary’s idea that “perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.” She connected the very personal feeling of wanting to reanimate to cutting-edge science of the time. Emotion and science combined.

Some have questioned whether it really was Mary who wrote Frankenstein’s story. When it was first published it didn’t have her name on the title page (as it was unusual for women to publish) and the oldest copy we have of the book is one with Shelley’s comments on it. But I believe it was her. From today’s perspective, we can see that Mary likely did have all she needed to write about creation, death and exclusion. It makes you wonder if she’d been questioned it if she’d been a man.

The novel made a huge sensation and has never stopped making a huge sensation

Isaac Asimov, American science-fiction writer

In 1818, joining Lord Byron again, the Shelleys left Britain for Italy. The couple sadly lost their second and third children. Mary finally gave birth one last time to her only surviving child, Percy Florence Shelley. During their time in Italy, Mary suffered from depression. This is not too surprising if you consider that she had given birth and lost children several times, lost a half-sister to suicide and was often excluded from society for not following the era’s marriage guidelines. Where Percy Byssche Shelley was seen as a fun Romantic with his fair share of affairs, Mary was often portrayed as a bit of a killjoy who cramped her husband’s style. An unfair portrayal in my opinion.

In 1822, Percy Byssche Shelly drowned at sea when his sailing boat sank during a storm. His body was up on the beach and was burned on a pyre. It is said that only his heart didn’t burn and that Mary took it in a handkerchief to keep in her desk drawer for the rest of her life. Mary is still only 24.

Mary and her son eventually returned to England. At 25, she is widowed and a single mother. Here she dedicates herself to raising her son and earning money with writing. Though not all is as conventional as it seems. There is a possibility she has an affair with Jane, the woman Percy was having an affair with at the time of his death, and being a woman who writes was still not very common. She continued to write for the rest of her life, such as the novels Mathilde or The Lost Man, but a large portion of her work was on assignment without mention of her name. Even though she had success with Frankenstein, publishers were still not very forthcoming with their support.

Mary’s remaining child, Percy Florence Shelley, eventually inherits from his rich grandfather, allowing him to support his mother in her later years. Mary died at 53, probably from a brain tumour, after several years of illness.

From plays as early as 1818, to The Rocky Horror Picture Show or Blade Runner, Mary Godwin Shelley’s work continues to inspire updates and interpretations. Her reference to Prometheus, the character from Greek myth who stole the fire from the gods, indicates that our fascination with humanity’s progress through technology and our risk of overreaching continues to resonate.

Also look up:

The 17th-century French novelist Madame d’Aulnoy came up with the term ‘comtes de fées’, which then gave the English language the term ‘fairy tales’.

Sources and other media:

- Podcast: ‘Frankenstein’, In Our Time, BBC Radio 4, 2020: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m00051n6#:~:text=In%20a%20programme%20first%20broadcast,his%20appearance%2C%20and%20never%20names

- Podcast: ‘Mary Shelley’, You’re dead to me, BBC Radio 4, 2020: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p08532gd

- Podcast: ‘1816, the Year Without a Summer’, In Our Time, BBC Radio 4, 2016: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b077j4yv

- Article: ‘Mary Shelley’s blighted life’, Victoria White, The Irish Times, 2000: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/mary-shelley-s-blighted-life-1.1117899

- Article: ‘Frankenstein at 200 – why hasn’t Mary Shelley been given the respect she deserves?’, Fiona Sampson, The Guardian, 2018: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jan/13/frankenstein-at-200-why-hasnt-mary-shelley-been-given-the-respect-she-deserves-

- Article: ‘How A Teenage Girl Became the Mother of Horror’, National Geographic, 2017: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2017/07-08/birth_of_Frankenstein_Mary_Shelley/

- Book: ‘Mary’s Monster: Love, Madness, and How Mary Shelley Created Frankenstein’, Lita Judge, 2018.

- Book: ‘She Made a Monster: How Mary Shelley Created Frankenstein’, Lynn Fulton, 2018.

- Film: ‘Mary Shelley’, Haifaa al-Mansour, 2017: