Gertrude Jekyll, born 1843, is known as a horticulturist and a holistic garden designer. She created hundreds of gardens in the UK, Europe and America, wrote dozens of books and countless articles on gardening. Her artistic approach to garden design is still respected today. She designed gardens in 3D, including multiple views and working across seasons. By using the colours and textures of various plants she brought a vibrancy to every corner of the garden. This style, the wild-looking English garden, fit in with her love of the Arts & Crafts movement and showcased the potential of gardens that opposed the rigidness of geometric French gardens. Her tombstone in Busbridge churchyard names her as an ‘artist, gardener and craftswoman’ because she was highly skilled at many different crafts. Gertrude spent most of her life in Surrey, England, where felt most at home, surrounded by her plants. In fact, most of Gertrude’s work was done from her home, through extensive correspondences with clients. This reminds us that working from home is not entirely new.

“A garden is a grand teacher. It teaches patience and careful watchfulness; it teaches industry and thrift; above all it teaches entire trust.”

Gertrude Jekyll

Gertrude didn’t start off solely dedicated to the botanical world. In 1861 she started the South Kensington School of Art (now the Royal College of Art), where she excelled at painting. She spent hours studying the works of impressionists like William Turner in the National Gallery, inspired by his use of colour. She painted daffodils and designed flower motif embroideries for friends. She designed wallpaper, did a spot of carpentry, designed jewellery and learned about gilding and wood inlay. Later, when Gertrude’s talents were stunted by severe and progressive myopia (near-sightedness), she switched careers and applied her training to gardening instead.

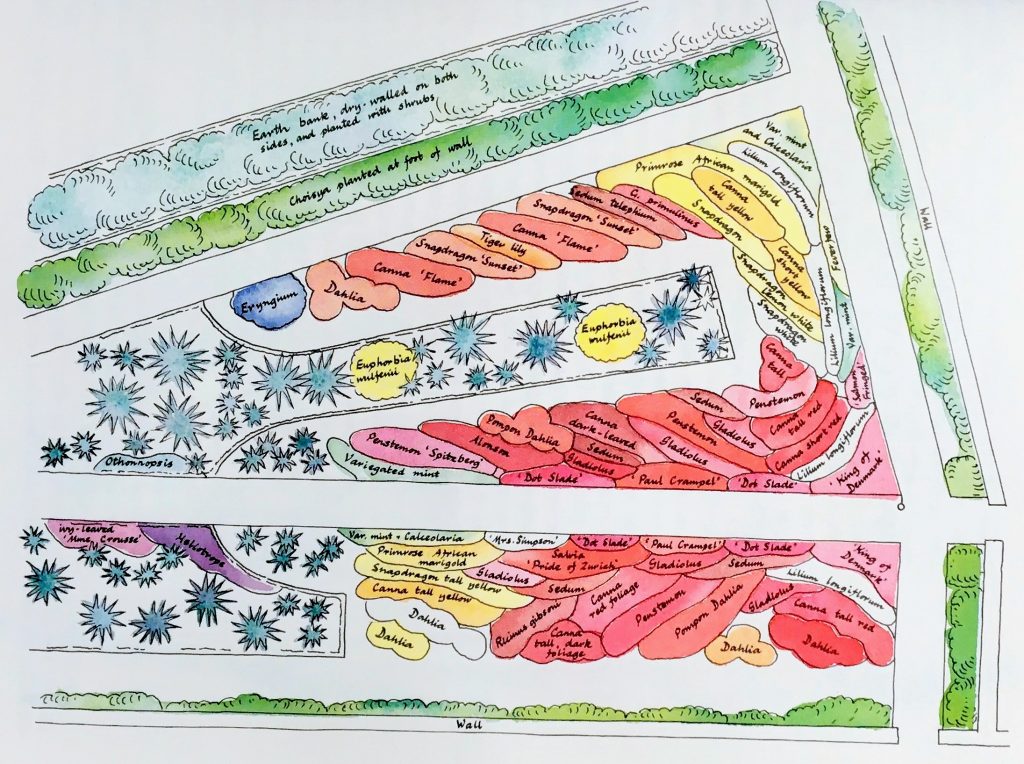

Gertrude’s approach to garden design was informed by her artistic training. Gertrude became known for considering colour palettes and contrasting plant textures. She chose plants that allowed for a lively garden across the seasons and made sure all vistas were interesting. Her green spaces were to be conceived us as a whole: “I am strongly of the opinion that possession of plants, however good, does not make a garden; it only makes a collection.” In order to involve each nook of the garden into her design, she would make a point to decorate the tricky and shadowy parts of the garden too. Borders were important to her, coming up with original plant combinations to soften the hard lines of formal gardens. Her huge herbaceous borders had colour schemes running from cold (white and blue) to hot (orange and red) and back to cold again. Her approach revalued ‘ordinary’ plants, like the Hostas, Bergenias, Lavender and old fashioned roses. In her later work, she would combine plants from the same biotope, to make borders less labour-intensive. The garden designer Beth Chatto would later also adopt this approach.

She never called herself a garden architect or designer. Instead, she saw the work she did as an interesting collection of tasks (designing, collecting knowledge about and growing plants) which resulted in a creative garden. Just like a painter knows their pigments, canvas and colours, she wanted to know about each aspect of the garden. In her own garden, she would experiment with plants herself first before recommending them to anyone else.

The love of gardening is a seed once sown that never dies

Gertrude Jekyll

Her circle of friends included influential figures like John Ruskin, William Morris, and watercolour artist Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, whose use of colour profoundly influenced her. A fun fact about the Jekyll family (she was fifth out of seven) is that her brother, Walter, was friends with Robert Louis Stevenson, the author who would borrow the family name for his famous Jekyll & Hyde story.

In 1882, Gertrude’s widowed mother, with whom she lived, gave her some land across the road from their house with the idea that Gertrude could eventually build her own house there. This plan led to an introduction to the young architect Edwin Lutyens by a rhododendron grower, for whom Edwin had designed a gardener’s cottage. Gertrude asked Edwin to design her house and the two became friends for life (Edwin affectionately called her ‘Bumps’). Together in her pony cart, they explored the landscape and architecture of southwest Surrey for inspiration. The result was Munstead Wood, one of Lutyens’ early masterpieces.

2. Gertrude Jekyll as painted by William Nicholson

Gertrude became increasingly involved in the gardens Edwin was designing for his houses, advising him on materials and supplying detailed planting plans. Though this seems obvious to us now, it was not common in the 19th century that a house and garden would be designed together. Most architects, like Reginald Blomfield, saw gardening as a necessary evil; the garden served the architect. Gertrude and Edwin were unusual in that the two influenced each other’s work, resulting in hundreds of Jekyll/Lutyens designs. Though many of these gardens were destroyed during the two world wars, the original plans and drawings made it possible for some to be restored: ‘Munstead Wood’ in Godalming, Surrey (where Gertrude used to live, restored by the current owners), ‘Le Bois des Moutiers’ in Varengeville sur mer, France, or ‘The Glebe House’ in Connecticut, USA.

The collaboration between Gertrude and Edwin Lutyens was due to their shared sense of humour, but also due to their shared love of the Arts & Crafts movement. They both admired traditional craftsmanship and paid special attention to detail.

2. Gertrude Jekyll’s gardening boots as painted by William Nicholson in 1920.

The Arts & Crafts movement was a response to the mass production and industry during the Victorian era when England was in its peak industrial and imperial growth. The Arts & Crafts movement championed all that was handmade, natural, personal, and traditional. Gertrude was a fervent supporter of the movement and knew many trades well herself. Before her eyesight failed, she knew how to thatch, carve and guild. She mastered fencing, walling, carpentry and metalworking. She even travelled to Italy, Greece and North Africa to learn how to tie carpets. She also took an interest in disappearing country crafts, collecting old household implements and recording their use. Her book ‘Old West Surrey’ includes her photographs and illustrations of the area’s old crafts and cottages from her trips around the county. Later on, when her extreme short-sightedness caused her to give up all of these crafts, she could still capture that which eyes could no longer see clearly with her photography.

“To plant and maintain a flower border, with a good scheme for colour, is by no means the easy thing that is commonly supposed.”

Gertrude Jekyll

Gertrude produced some 2000 design drawings for over 250 gardens, showcasing her versatility and attention to detail. It also shows how hard she had to work to realize the seemingly spontaneous lushness of her gardens. She believed passionately in the understanding of beauty in the natural landscape and strived to create it in her work. Throughout different settings, her designs involved plants to achieve the most natural effect. She would meticulously design the garden down to the smallest corner.

Gertrude’s work isn’t restricted to garden designs and drawings, she also wrote books and contributed over 1000 articles to Robinson’s periodical, The Garden, and Gardening Illustrated and Country Life. Her books were often illustrated with her own photographs and drawings, all based on her own experience. Her books, like ‘Colour Schemes for the Flower Garden’ described her own gardening attempts and learnings. Her hands-on and personal practical approaches made her gardening book more engaging and popular than most.

If anything, she taught us to enjoy the little things: “I plant rosemary all over the garden, so pleasant is it to know that at every few steps one may draw the kindly branchlets through one’s hand, and have the enjoyment of their incomparable incense; and I grow it against walls, so that the sun may draw out its inexhaustible sweetness to greet me as I pass.”

Also look up:

Others who designed gardens, grew plants and helped create green spaces are Beth Chatto and Kate Sessions. The Dutch landscape and garden architect Mien Ruys is, together with other like Piet Oudolf, considered a leader in the “New Perennial Movement.”

Sources and other media:

- Article: ‘style icon: gertrude jekyll’, Amy Azzarito: https://www.designsponge.com/2012/05/style-icon-gertrude-jekyll.html

- Article: ‘Gertrude Jekyll’, Exploring Surry’s Past: https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/people/gardeners/gertrude_jekyll/

- Article: ‘Colour Schemes for the Flower Garden’: https://www.theexaminedlife.org/library/colour-schemes-for-the-flower-garden/

- Website: https://gertrudejekyll.co.uk/

- Website: ‘Gertrude Jekyll’, Goldalming Museum: http://www.godalmingmuseum.org.uk/index.php?page=gertrude-jekyll

- Article: ‘Gertrude Jekyll’, Mooie Tuinen: https://www.mooietuinen.be/gertrudejekyll.html

- Video: ‘The History of Women and Art – Episode 3 of 3’, Prof. Amanda Vickery, BBC Two, 2014: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=00hAYlpm2yY