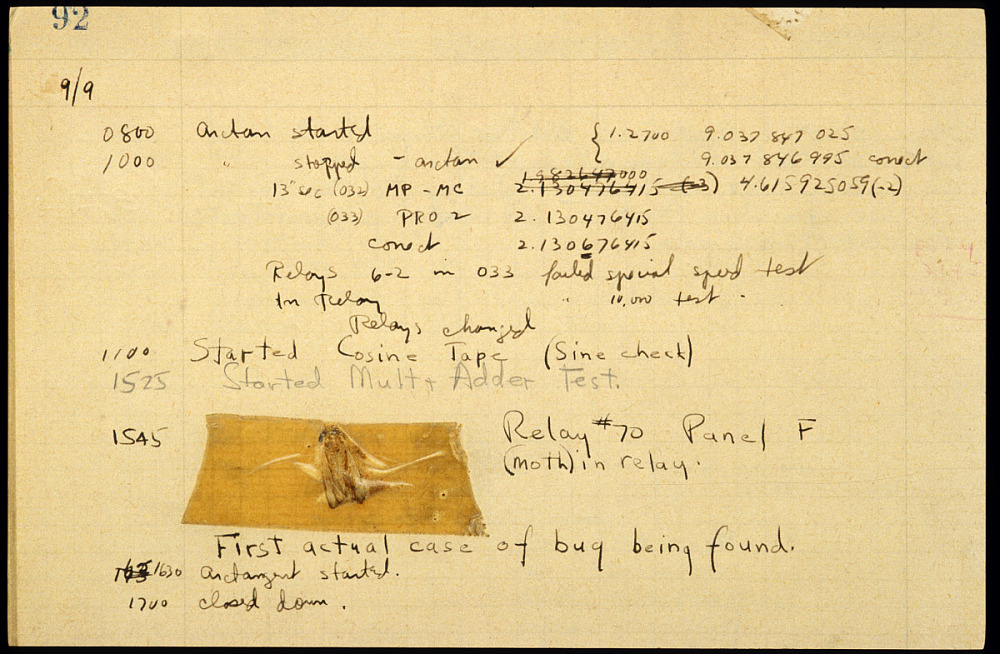

Grace Hopper was one of the first modern computer programmers, a central figure in the development of computers and a key player in evolving programming language. It was also Grace who first ‘debugged’ a computer, coining the term ‘bug’ for a computing malfunction, when she picked an actual bug out of the hardware of a machine.

She was a girl with great curiosity, born Grace Brewster Murray in New York City in 1906. Her mother remembered she would take apart electrical items, like her alarm clock, to understand how they worked. Eventually, she also knew how to put them back together again. She took this self-taught engineering knowledge to Vassar College, where she graduated in mathematics and physics. By 1934 she’d earned a PhD in mathematics from Yale University, the first woman to do so. From there, Grace took a job teaching at Vassar College.

A ship in port is safe, but that’s not what ships are built for.

Grace Brewster Hopper

During WW2, Grace left Vasser to join the US Navy Reserve, or the Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service) to be more precise. In 1944 she was assigned to work with Prof. Howard Aiken at the Harvard Computation Laboratory. The team made and worked on the Harvard MARK I, a giant calculator and early prototype of the electronic computing machines. Grace wrote its 500-page manual, outlining the fundamental operating principles of computers.

2. Grace Murray Hopper sitting at desk in the Computation Lab. Source: NMAH Archives Center Grace Murray Hopper Collection

Grace stayed at Harvard until after the war, having become a research fellow on the Harvard faculty in the meantime. In 1949 she joined the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, led by the designers of the ground-breaking ENIAC computer system developed during the war, the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer. Here Grace was involved in the creation of UNIVAC, a line of electronic digital stored-program computers designed for commercial use. She invented the first computer compiler, a program that translates written instructions into codes that computers read directly. In her paper, ‘The Education of a Computer’, she outlines how her compiler automatically created code by using a catalogue of sub-routines (pseudo code), saving operators programming time. The compiler reduced the time spent creating individually crafted programmes from weeks to hours. The aim of the A-0 compiler, which would evolve into the A1, A-2 and finally the B-0, was to ease everyday routines by writing programmes that used English commands and vocabulary instead of mathematical symbols. The benefit was that other manufacturers could use it too, creating a standard.

Her work on the compiler led her to co-develop the COBOL, one of the earliest standardized computer languages. COBOL enabled computers to respond to words in addition to numbers. This easy-to-use ‘language’ is probably the most successful programming language for business applications in history. It helped launch the exponential growth of inventions in computer sciences, leading up to the information revolution.

Hopper retained her affiliation with the Naval Reserve, getting a call back in 1967. By the time she retired, in 1986, she had risen to be a Rear Admiral. Being passionate about what she did, she was then hired as a senior consultant to Digital Equipment Corporation, a position she kept until her death in 1992.

I think I always looked for the easiest and best, most accurate way of getting something done. I don’t use high-level theory. I use very basic common sense – the whole original concept of the compiler is the most common-sense thing I ever heard of. And I’ve always said that if I hadn’t done it, somebody else was bound to sooner or later. It was so common sense that it had to be done.

Grace Hopper interviewed by Angline Pantages (1980), Computer History Museum, Maryland.

Grace Hopper loved teaching. She gave up to 300 lectures per year on computers, often using humour. She predicted that computers would one day be small enough to fit on a desk and people who were not professional programmers would use them in their everyday life. She was right about that!

Grace’s contribution to the development of computing machines is recognised by many. There’s a U.S. Navy destroyer called the USS Hopper (DDG-70), a Cray XE6 “Hopper” supercomputer, she was named a distinguished fellow of the British Computer Society (at the time the first and only woman to hold the title), she received the US National Medal of Technology in 1991 and, in 2016, Grace Hopper was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Also look at

The other founding lady of computing is Ada Lovelace, who I covered previously. Margaret Heafield Hamilton is another American computer scientist and system engineer. She coined the term ‘software engineering’. Please let me know if there are any other names I should mention.

Sources and other media

- Article: ‘Grace Murray Hopper’, Computer History Museum: https://computerhistory.org/profile/grace-murray-hopper/

- Article: ‘Grace Murray Hopper’, Yale News: https://news.yale.edu/2017/02/10/grace-murray-hopper-1906-1992-legacy-innovation-and-service

- Article: ‘Grace Hopper’, Sampo Seppä, 2018: https://shethoughtit.ilcml.com/biography/grace-hopper/

- Book: ‘Grace Hopper, Queen of Computer Code’, Laurie Wallmark, 2017.