Nana Asma’u was an 18th-century Islamic Fulani scholar, poet and educator in what is now Northern Nigeria. She championed education for women and created a legacy of female educators.

Nana was born in Degal, North-Western Nigeria, into what became a powerful family. Her father, Shehu Usman dan Fodio, was a prominent Islamic scholar and teacher preaching in Gobir, one of the Hausaland kingdoms. When Usman was exiled by the Gobir King Yunfa as a threat to his power, this kickstarted the Fulani War. Between 1804 and 1808 Usman and his followers conquered a significant territory and set up a Caliphate. Nana lived through this war, the expansion of the resulting Sokoto Caliphate in Hausaland and the establishment of the city of Sokoto as the seat of power by her brother Muhammad Bello, her father’s successor.

The clan name ‘Fodio’ means ‘learned’, so it should be no surprise that Nana received a great education. Taught by her father, uncle and a circle of related scholarly Fulani women, including the female scholar Aisha, Nana became knowledgeable about Quranic teachings. She was well-versed in three different languages: her first language Fulfude, the generalist Arabic, and the regional Hausa – all using the Arabic script. She also spoke the Taureg language Tamachek. Useful, when you want to spread your teachings.

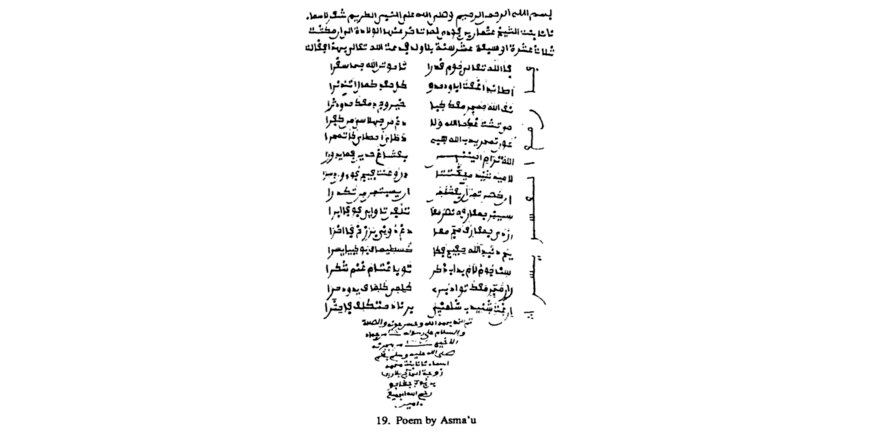

Not only did Nana get married, have six children and run a large household (of hundreds!), she was also a prolific writer of poems. The tumultuous events and colourful characters of her childhood were reflected in her lengthy poems. Many of her writings were about the Caliphate, on its founding principles, rules, history and her family’s associated religious legacy. She also wrote about divine truth and Sufi women saints. In fact, many of her poems emphasised female leadership and the rights of women within the community’s ideals of Islamic law and the Sunnah (the sayings and practices of the Prophet Muhammad). Other topics included law, medicine and the importance of education.

She was on a mission – and everyone was included.

Natty Mark Samuels, Founder of ‘African School’

In Hausaland it was common for girls to be married off by the time they were thirteen, at which point their education usually ended. But Nana had always had supportive men around her and was able to continue her education. This meant that she knew what education could do for women. In the 1830s she set up the Yan Taru, a programme aimed at making education accessible to all, especially women. Her poems were used as teaching aids, with Qur’anic rhyme and rhythm, designed to make them easy to memorise. Having these available in multiple languages made her work accessible to different communities.

Muslim women of Northern Nigeria have historically had only very limited access to education although occasionally exceptional individual women have had the opportunity to excel in Islamic learning – the most notable example being Nana Asma’u.

Muhammad S. Umar, scholar

The Yan Taru concept was a collective of travelling female teachers called jajis, trained by Nana, who ventured to towns and rural villages to teach at people’s homes. Each of these women received a malfa, a woven hat tied with a red turban, to make them part of the Yan Taru ‘brand’. These Yan Taru teachers brought literacy into the homes of women who would otherwise likely miss out on an education. Due to this programme, Nana set up a tradition of women as teachers of Islamic religious knowledge. Although they also taught those who belonged to other faiths, it fits into the larger political programme of conversion. To this day, her teachings are recited and schools bear her name. Her legacy, of a woman’s right to education, continues to be relevant and remains as a practice.

Due to her central role in the family, Nana also corresponded with foreign scholars and dignitaries throughout the sub-Saharan African Muslim world. It shows she was an important political figure, serving as a record keeper, mediator and advisor to her ruling family members. Her many religious poems were also part of a political purpose: her father aimed to centralise and reform the fragmented practice of Islam in Hausaland and convert more of his subjects. Her work helped to shape this new community’s orthodox religious practice. The family was part of the Qadiriyya order, focused on the pursuit of knowledge as a spiritual path.

Nana Asma’u lived into her seventies, making her the longest surviving member of Shehu’s family. It’s due to her writings we know so much about the history of the Sokoto Caliphate, her work functioning as an archive (like the eulogies she wrote, which are now valuable historical insights into the turbulent era). Her work helped shape the Caliphate at the time and solidified her legacy of scholarship by women in the region.

The Sokoto Caliphate still exists, though now as a part of the nation-state Nigeria. The Sultan has a bridging role, connecting national politics to the majority Muslim conservative population. It seems as though the freedom of women is not quite what Nana and her family had envisioned. The culture has become more conservative and sadly “only 25% of Northern Nigerian girls proceed to secondary school“, according to the Sahara Reporters. Not all history is about progress.

Also look up

There are other notable Islamic women involved in education and knowledge, like Rabi’ah Bint Mu’awwad, a scholar and teacher of Islamic law in Medina, A’isha bint Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, who was learned in the Islamic sciences and a respected teacher who had many famous scholars as her pupils or Fatima al-Fihri, who founded a mosque that became a university.

SOurces and other media

- Summary article: ‘Nana Asma’u’, Alaine Hutson: https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-468

- Book: ‘Chapter Four: Mass Islamic Education and Emergence of Female ‘Ulama’ in Northern Nigeria: Background, Trends and Consequences’, Muhammad S. Umar, in ‘Islam in Africa, Volume 2: The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa. Edited by Scott S. Reese, BRILL, 2004: https://books.google.nl/books?id=zP5Zk8ixR3QC&pg=PA99&lpg=PA99&dq=Nana+Asma%E2%80%99u+Alaine+Hutson&source=bl&ots=jQ_zrFreDq&sig=ACfU3U0QgrPkOGcQ9O0ke87lTzfhQVWqxg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjTnq3TgbjwAhVCsKQKHbUhBJkQ6AEwBHoECAIQAw#v=onepage&q=Nana%20Asma%E2%80%99u%20Alaine%20Hutson&f=false

- Article: ‘Ode to Nana Asma’u: Voice and Spirit’, Natty Mark Samuels, 2016, Muslim Heritage: https://muslimheritage.com/ode-to-nana-asmau-voice-and-spirit/

- Article: ‘Nana Asma’u: princess, poet, reformer of Muslim women’s education’, Keri Engel, Amazing Women in History: https://amazingwomeninhistory.com/nana-asmau-princess-poet-reformer-muslim-womens-education/

- Article: ‘Oxford Bibliographies: Nana Asma’u bint Usman ‘dan Fodio’, Beverly Mack, 2019, Oxford Biographies: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195390155/obo-9780195390155-0262.xml

- Article: ‘#100AFRICANWOMENWRITERS: 4. NANA ASMA’U’, Booksky, 2017: http://www.bookshybooks.com/2017/03/100africanwomenwriters-4-nana-asmau.html

- Article: ‘Nana Asma’u gaf vrouwen hun recht op onderwijs terug’, Irene Schippers, Qantara, 2017: https://www.qantara.nl/mens-en-maatschappij/politiek-en-geschiedenis/nana-asmau-1793-1864-gaf-vrouwen-hun-recht-op-onderwijs-terug/

- Article: ‘Honouring the Yan – Taru Legacy of Nana Asma’u Bint Uthman Dan Fodio’, Wardah Abbas, Amaliah, 2019: https://www.amaliah.com/post/51230/honouring-yan-taru-legacy-nana-asmau-bint-uthman-dan-fodio

- https://chnm.gmu.edu/wwh/p/214.html

- Podcast: ‘Beautiful Minds: Nana Asma’u’, Enclopedia Womannica, 2019: https://encyclopedia-womannica.simplecast.com/episodes/beautiful-minds-nana-asmau-NkxhMFSc

- News story: ‘Only 25% of Northern Nigerian Girls Proceed to Secondary School’, Sahara Reporters, 2021: http://saharareporters.com/2021/07/30/only-25-northern-nigerian-girls-proceed-secondary-school-%E2%80%93-survey

- Website: yantaru.com

One Comment

Comments are closed.