The title ‘scientist’ was first used to describe the Scottish mathematician, geographer and astronomer Mary Fairfax Somerville. She was a polymath with an interdisciplinary approach who was “one of the most distinguished astronomers and philosophers of the day” (London Morning Post, 1872). Though her work mostly focussed on light in the solar system and paved the way for the discovery of Neptune, it was her style of writing which really set her apart. She was respected for her knowledge but famous for the ability to describe complexity with clarity and making the sciences accessible.

the queen of nineteenth-century science

London’s Morning Post

Born in 1780, Mary mostly spent her childhood in Burntisland, across the water from Edinburgh. Her father, a navy man, was often away and her mother showed not interested in her education. So Mary roamed the area and collected fossils and shells, fascinated by the natural world around her. Though Mary received some basic education at a boarding school, her real education came from her uncle, who taught her Latin, and her brother’s tutor, who taught her algebra. She was an eager student, reading whatever she could get her hands on. She went on to study art with Alexander Nasmyth in Edinburgh, where was introduced to Euclid’s Elements of Geometry. This, according to her teacher, was important to understand perspective and mechanical science. It was Mary’s gateway to mathematics and astronomy. Staring at the night sky, she wanted to learn and master the rules of the universe.

Mary was stopped from doing further study when her sister died and her parents thought studying had contributed to her death. Her passion for science and study was also considered unladylike. Apparently, her father worried that “the strain of abstract thought would injure the tender female frame.” She continued to study in secret instead. In public, she maintained her role of being the polite and well-mannered daughter, continuing her social duties and attending events. In addition to needlework, she learned how to play the piano and gained the nickname ‘the Rose of Jedburgh’.

In 1804 she was married off to a distant cousin, the Russian Consul in London, Captain Samuel Greig. They lived in London and had two children. But the marriage seems to have been an unhappy one. Her husband did not appreciate Mary’s pursuit of scientific knowledge and she was forced to stick to domestic duties. Upon her husband’s death, just a few years later in 1807, Mary returned to Scotland. With a small inheritance and a status as a widow, she had some freedom to study again.

I resented the injustice of the world in denying all those privileges of education to my sex which were so lavishly bestowed on men.

Mary Somerville

Another few years later she married another cousin, Dr William Somerville, who did support her studies of the physical sciences. She had another four children with him, but also managed to find time to meet the most eminent scientific men of the time. Having returned to London, her supportive husband helped her get access to scientific circles. Mary also tutored Lady Byron’s daughter Ada Lovelace and introduced her to Charles Babbage, who would develop one of the first computing machines.

Mary’s knowledge and talent did not go unnoticed. Her big break came when she was asked by Lord Brougham to translate ‘Traité de mécanique céleste’ by Pierre-Simon Laplace for the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. She said: “I translated Laplace’s work from algebra into common language”. Published in 1831 as ‘The Mechanism of the Heavens’, it not only included Laplace’s work but Mary’s own additions and interpretations. The work made her famous. The first American female astronomer Maria Mitchell called her “the most learned woman in Europe”.

Her works included ‘On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences’ (1834), ‘Physical Geography’ (1848), which was commonly used as a textbook until the early 20th century, and ‘Molecular and Microscopic Science’ (1869). In fact, her work was the backbone of Cambridge University’s first science curriculum and her writings were some of the most popular scientific publications of that time.

In 1834, when reviewing Mary’s bestseller ‘On the Connection of Physical Sciences’, William Whewell coined the term ‘scientist’. Getting rid of the cumbersome terms ‘man of science’ or ‘natural philosopher’, he simultaneously invented a gender-neutral term. Known for his wordsmithing, Whewell used the term to refer to someone who advances knowledge and is interdisciplinary in their approach. Mary’s work brought together maths, astronomy, geology, chemistry and physics; connecting previously fragmented or separate disciplines. Her creative thinking links the word “scientist” to the term “artist”.

Her easy writing style gave her work a broad appeal. Her writings were clear, her descriptions were concise and her work had an underlying enthusiasm that could not go unnoticed. ‘On the Connection of Physical Sciences’ brought together the latest from every branch of scientific research and presented it in clear language to a mass audience. Meanwhile, keep in mind, she was also raising a family.

While her head is up among the stars, her feet are firm upon the earth

Novelist Maria Edgeworth, after reading The Mechanism of the Heavens

Mary studied the solar system with incredible accuracy. Her detailed studies led her to notice a wobble in the orbit of Uranus and suggested there could be another planet out there. She was right: it was the planet Neptune. John Couch Adams, who was influenced by Mary’s writings, would go on to investigate her comments and confirmed her hypothesis.

In 1835, Mary and the astronomer Caroline Herschel were the first women to become honorary members of the Royal Astronomical Society. This sadly did not mean that they were allowed into the building; Mary’s husband read her article on magnetism and sunlight to the Society on her behalf.

2. Portrait for Mary Somerville by Thomas Phillips

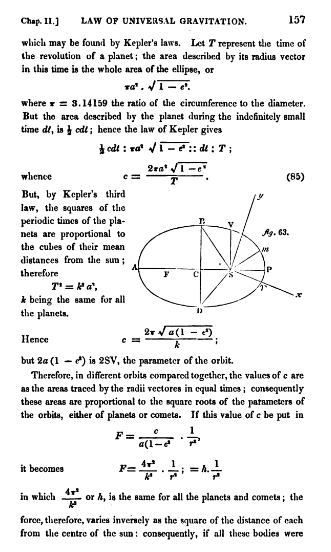

3. Page 157 from Mechanism of the Heavens, where Mary discusses the law of universal gravity and Kepler’s laws of planetary motion.

In this same year, she received a £300 pension from the government, a recognition of her contribution to the sciences. A few years later, she and her husband moved to Italy, where she spent much of the rest of her life. She died in Naples in 1872 at 91.

Besides being a scientist, Mary was a feminist and opposer of slavery. When the philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill organised a major (yet sadly unsuccessful) petition at Parliament for votes for women, he asked Mary Somerville to sign it first. She was a major figure at the time and he knew she was known to champion rights for women, especially education for women. She also refused to drink sugar in her tea as a protest against slavery.

In Oxford, the formerly women-only Somerville College was named after Mary for her involvement with education for women. She also has other buildings, an asteroid belt and a lunar crater named after her. She featured on the £10 note of the Royal Bank of Scotland, the first non-royal woman to do so. Mary’s obitiary in the 1872 London Morning Post read: “one of the most distinguished astronomers and philosophers of the day”.

Also look at

A slightly older contemporary of Mary was the Chinese astronomer Wang Zhengy. She used mirrors and lamps to show the blocking of the moon or earth creating lunar and solar eclipses. Ada Lovelace, a woman that Mary tutored, went on the be the first person to recognise the possibilities of computer programming. Caroline Herschel, a contemporary of Mary’s, was an astronomer who worked together with her brother and discovered several comets from her home in Hannover. Mary was also once visited by Maria Mitchell, an American astronomer, librarian, naturalist, and educator. In 1847, she discovered a comet later known as “Miss Mitchell’s Comet” in her honour. Another, slightly older, contemporary of Mary was the astronomer Wang Zhengy, who

Sources and other media

- Article: ‘Tenacity, the Art of Integration, and the Key to a Flexible Mind’, Maria Popova, Brainpickings, 2020: https://www.brainpickings.org/2020/10/20/mary-somerville/

- Podcast: ‘Mary Somerville: The queen of 19th-Century science’, The Forum, BBC: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3ct1rm3

- Article: ‘Meet Mary Somerville: The Brilliant Woman for Whom the Word “Scientist” Was Coined’, Maria Popova, Brainpickings, 2016: https://www.brainpickings.org/2016/12/26/mary-somerville-scientist/

- Article: ‘Mary Fairfax Greig Somerville’, J.J. O’Connor and E.F. Robertson, MacTutor, St.Andrews, 1999: https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Somerville/#reference-13

- Article: ‘Mary Fairfax Somerville, Queen of Science’, Elisabetta Strickland, Notices of the AMS, September 2017, Vol. 64, Nr 8: https://www.ams.org/journals/notices/201708/rnoti-p929.pdf

- Article: ‘Mary Somerville’, Patricia Fara: https://scientificwomen.net/women/somerville-mary-88

- Article: ‘The Three Marys: The women who unlocked Earth, space and life’, Rory Cockshaw, Varsity, Cambridge, 2020: https://www.varsity.co.uk/science/18660

- Book: ‘Toksvig’s Almanac: An eclectic meander through the historical year’, Sandi Toksvig, 2021.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.